klein ist’s man sieht es kaum

singt doch so schön, dass wohl von nah und fern alle die Leute gern kommen und …

klein ist’s man sieht es kaum

singt doch so schön, dass wohl von nah und fern alle die Leute gern kommen und …

„I’s gone!“ sighed the Rat, sinking back in his seat again. „So beautiful and strange and new! Since it was to end so soon, I almost wish I had never heard it. For it has roused a longing in me that is pain, and nothing seems worth while but just to hear that sound once more and go on listening to it for ever. No!

There it is again!“ he cried, alert once more. Entranced, he was silent for a long space, spellbound.

„Now it passes on and I begin to lose it,“ he said presently. „O, Mole! the beauty of it! The merry bubble and joy, the thin, clear happy call of the distant piping! Such music I never dreamed of, and the call in it is stronger even than the music is sweet! Row on, Mole, row! For the music and the call must be for us.“ The Mole, greatly wondering, obeyed. „I hear nothing myself,“ he said, „but the wind playing in the reeds and rushes and osiers.“

The Rat never answered, if indeed he heard. Rapt, transported, trembling, he was possessed in all his senses by this new divine thing that caught up his helpless soul and swung and dandled it, a powerless but happy infant in a strong sustaining grasp.

In silence Mole rowed steadily, and soon they came to a point where the river divided, a long backwater branching off to one side. With a slight movement of his head Rat, who had long dropped the rudder-lines, directed the rower to take the backwater. The creeping tide of light gained and gained, and now they could see the colour of the flowers that gemmed the water’s edge.

„Clearer and nearer still,“ cried the Rat joyously.

„Now you must surely hear it! Ah – at last – I see you do!“

Breathless and transfixed the Mole stopped rowing as the liquid run of that glad piping broke on him like a wave, caught him up, and possessed him utterly. He saw the tears on his comrade’s cheeks, and bowed his head and understood. For a space they hung there, brushed by the purple loosestrife that fringed the bank; then the clear imperious summons that marched hand-in-hand with the intoxicating melody imposed its will on Mole, and mechanically he bent to his oars again. And the light grew steadily stronger, but no birds sang as they were wont to do at the approach of dawn; and but for the heavenly music all was marvellously still.

On either side of them, as they glided onwards, the rich meadow-grass seemed that morning of a freshness and a greenness unsurpassable. Never had they noticed the roses so vivid, the willowherb so riotous, the meadow-sweet so odorous and pervading. Then the murmur of the approaching weir began to hold the air, and they felt a consciousness that they were nearing the end, whatever it might be, that surely awaited their expedition.

Kenneth Grahame: The wind in the willows – 1908

„The bank is so crowded nowadays that many people are moving away altogether. O no, it isn’t what it used to be, at all. Otters, kingfishers, dabchicks, moorhens, all of them about all day long and always wanting you to do something – as if a fellow had no business of his own to attend to!“

Kenneth Grahame: The wind in the willows – 1908

„Nice? It’s the only thing,“ said the Water Rat solemnly, as he leant forward for his stroke. „Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing – absolutely nothing – half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats. Simply messing,“ he went on dreamily:

„messing – about – in – boats; messing -„

„Look ahead, Rat!“ cried the Mole suddenly.

It was too late. The boat struck the bank full tilt.

The dreamer, the joyous oarsman, lay on his back at the bottom of the boat, his heels in the air.

„- about in boats – or with boats,“ the Rat went on composedly, picking himself up with a pleasant laugh.

„In or out of ‚em, it doesn’t matter. Nothing seems really to matter, that’s the charm of it.“

„Whether you get away, or whether you don’t; whether you arrive at your destination or whether you reach somewhere else, or whether you never get anywhere at all, you’re always busy, and you never do anything in particular; and when you’ve done it there’s always something else to do, and you can do it if you like, but you’d much better not.“

„Look here! If you’ve really nothing else on hand this morning, supposing we drop down the river together, and have a long day of it?“

The Mole waggled his toes from sheer happiness, spread his chest with a sigh of full contentment, and leaned back blissfully into the soft cushions. „What a day I’m having!“ he said. „Let us start at once!“

Kenneth Grahame: The wind in the willows – 1908

“ … ich finde, es ist besser, du bleibst hier und entschuldigst dich, statt nach Kalormen zurückzukehren.“

„Für dich mag das ja angehen“, jammerte Bree.

„Du hast dich nicht unehrenhaft verhalten. Aber ich habe meine Ehre verloren.“

„Mein liebes Pferd“, sprach der Einsiedler, der sich auf dem taubesetzten Gras lautlos genähert hatte.

„Mein gutes Pferd, du hast lediglich deinen Hochmut verloren.“

„Nein, nein, mein Neffe. Es besteht kein Grund, die Ohren zurückzulegen und die Mähne gegen mich zu schütteln. Wenn du dich wirklich so gedemütigt fühlst, dann musst du lernen, deine Ohren der Vernunft zu öffnen.“

„Du bist nicht das großartige Pferd, für das du dich hieltst, als du noch mit den armen, stummen Pferden zusammenlebtest. Natürlich warst du mutiger und klüger als sie.“

„Aber deshalb bist du in Narnia noch lange nichts Besonderes.“

„Solange du aber weißt, dass du nichts Besonderes bist, wirst du alles in allem doch ein recht annehmbares Pferd sein.“

C. S. Lewis: Die Chroniken von Narnia / Der Ritt nach Narnia, aus dem Englischen von Ulla Neckenauer, published by Carl Ueberreuter GmbH under license from the C. S. Lewis Company Ltd.

Kraniche oder Gänse?

Beide fliegen gerne in Keilformation oder schrägen Linien.

Die hier sind Kraniche

Kraniche trompeten.

haben lange Beine, die über den Körper hinausragen

Flügel wie Bretter mit langen schwarzen Federn an den Enden.

Graugänse schnattern und quäken

segeln fast nie sondern schlagen häufig mit den Flügeln

Flügel abgeschrägt

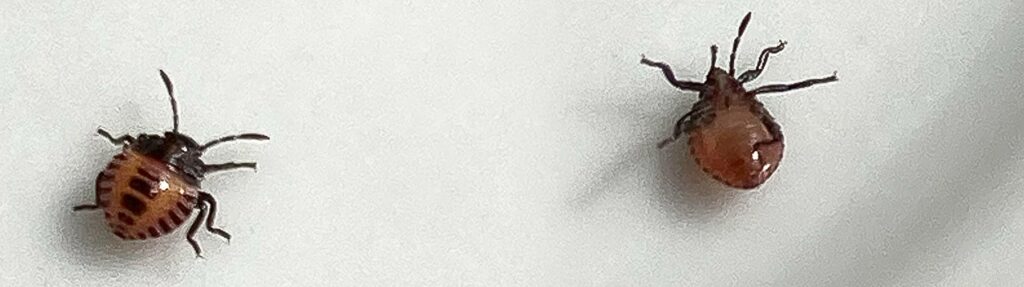

2022 ist das Jahr der Wanzen.

Stink Bug Nymphs

There is something cheery in its very dinginess, and something free and elfin in its very insignificance.

g. K. Chesterton, The wisdom of father Brown: the head of ceasar, Bloomsbury Books London